Growth Beyond the Ladder

I consider myself lucky to have experienced the abject chaos of high growth Silicon Valley tech companies in the 2010s. You know, the good ol’ days when investors were willing to throw millions at overhyped nonsense like Juicero (this will never not be funny to me), yearly compensation increases were a given (with separate budgets for both merit and cost of living!), and headcount was not only free, but you could manifest it on the spot for an “opportunistic hire.”

Every company I worked for during that decade was going through what we boastfully called hypergrowth, which meant that I was going through hypergrowth. There was no shortage of challenging technical problems to solve, organizational fires to put out, and new investments to make. As my organizations’ headcount grew, so did I – in both experience and title.

Of course, things feel a bit different a decade later. Investors are warier and budgets are tighter. Organizations are flattening with every new layoff, and people are being asked to do more with less. There are fewer opportunities for promotion and far fewer leadership positions available for employees who have more potential than they do experience. For some of you, this is a hard time to be a manager.

Whether your current job feels stagnant, chaotic, or somewhere in between, this post is for those of you who want structure beyond a job ladder when you talk about growth with your team.

Promotions != Growth

You already know the vibe the moment a direct report tells you they want to have a growth conversation. They’re likely about to ask for your guidance on securing a promotion; what’s the checklist of things they need to do to gain organizational support for a title bump and, presumably, an accompanying pay increase? If you’re lucky, you have a job ladder to point to, a regular feedback cycle where promotion nominations are discussed, and all of the conditions that allow someone to prove their performance at the next level. If you don’t have those things (and honestly, even if you do!), it’s time to reframe how you think and talk about growth.

“Promotions are not growth. Promotions are a single outcome of growth.”

Once during a performance calibration discussion, a coworker said something that really stuck with me: “Promotions are not growth. Promotions are a single outcome of growth.” This might sound annoying coming from me, given that my resume literally looks like an Engineering job ladder. But as someone who has both witnessed and played a part in the growth of hundreds of employees over the years, I know that real, satisfying professional growth takes on many forms.

A promotion implies growth. But so does a lateral move or a role change. A change in specialization or scope implies growth. An increased presence in executive meetings or a new set of responsibilities can both signal growth.

And by the way, these other outcomes I just mentioned can be a solid justification for an eventual promotion, so you shouldn’t lose sight of that. But when organizational constraints limit the levers you can pull for your team, it’s best to take our promotion blinders off and focus on the outcomes that are within our control. How can we focus our energies on growth outcomes that may not fully satisfy one’s (very valid) desire to climb the ladder, but will still keep them feeling engaged and challenged at work?

The importance of stretch assignments

According to the popular 70:20:10 learning model, the vast majority of our learning, growth, and development happens via “experience,” which refers to situational learning that happens as part of doing a job. Janice Fraser covers this in one of my favorite conference talks of all time, Female Career Advancement Summed up in One Usable Diagram. In this talk, she does a deep dive into the research that shows just how important stretch assignments are to workplace advancement, as well as the factors that make these assignments disproportionately available to men. (Note: while I am not aiming for this post to be a treatise on gender bias in career advancement, it’s Fraser’s thorough research that introduced me to the 70:20:10 model, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t take the opportunity to point out just how important it is that we consciously give everyone equal access to stretch assignments. If you still want a treatise on gender bias you can start with my post on Disrupting Bias in Feedback and watch Fraser’s talk linked above.)

A stretch assignment is something that takes someone just outside of their comfort zone – stretchy enough to challenge them into learning and doing something new, but not so stretchy that they are set up for failure.

Fraser defines stretch assignments succinctly: “It’s something you don’t already know how to do.” A stretch assignment is something that takes someone just outside of their comfort zone – stretchy enough to challenge them into learning and doing something new, but not so stretchy that they are set up for failure.

When I think about stretching someone, I think about the various axes on which they can expand. We may not be able to offer a perfectly packaged “staff level project” to the Senior Engineer who wants a Staff Engineer promotion, so instead, we need to think about what we can offer them that will help them expand.

Expansion axes to consider:

Skills: Can this person pick up a new skill, like public speaking or vibe coding? Can they go deeper on an existing skill and become the go-to expert?

Scope: Can they increase the timescale of their tasks (e.g. working on month-long goals vs week-long tasks)? Can they expand their breadth of expertise, like a backend engineer picking up frontend skills so that they can deliver a full feature on their own?

Complexity: Can they create and execute on clear plans from projects that have significant ambiguity? Can they own initiatives that require complex coordination across multiple business units?

Business Impact: Can they be granted explicit leadership responsibility for business goals, especially those without defined solutions? Can they improve metrics the C-suite cares about?

Influence: Can they lead cross functional initiatives that will expose them to other business leaders and executives? Can they take a successful team practice and expand it to other teams at scale?

In conversations with your direct report, use this framing to brainstorm projects, initiatives, or opportunities that will stretch them in at least two of these categories. It’s important that you do this with your team member, as they may have personal goals you’re unaware of! Your job as a boss is to help them find alignment between their personal goals and business needs.

Limiting factors in delegation

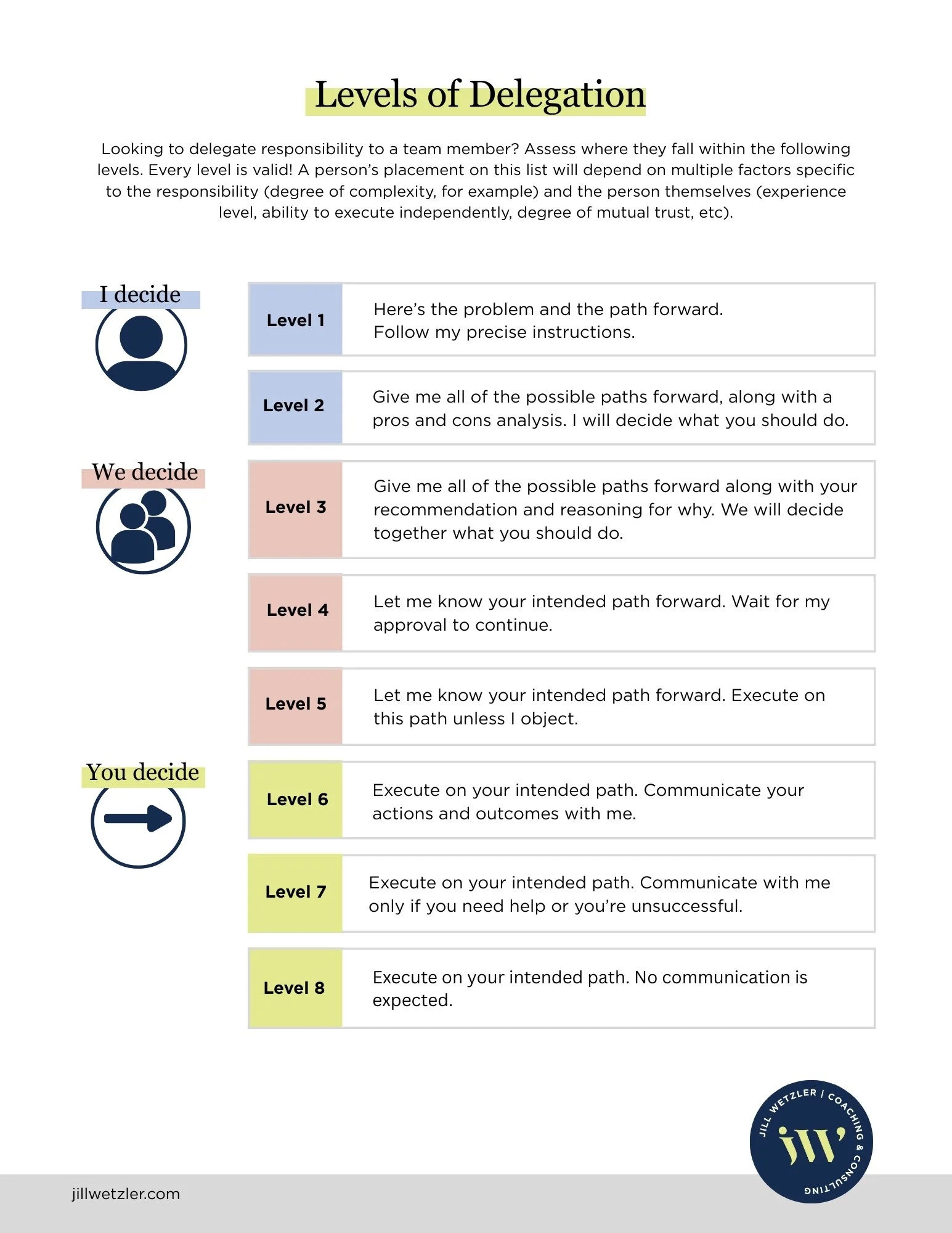

Once we have our stretch assignment(s) in mind, it’s time to delegate. If you haven’t already read my post on delegation, I suggest bookmarking it for later. In the meantime, here’s a quick recap of the Levels of Delegation I introduced:

There are two ways the Levels of Delegation help us think about growth:

For existing responsibilities, we aim to continually move someone to higher levels, so that they become more autonomous and exhibit greater ownership.

For stretch assignments, we aim to give them new responsibilities that will organically place them into lower levels, so that we can start moving them up again.

Remember that when we are offering someone a stretch assignment, the goal is to be stretchy but not too stretchy. If we delegate to someone at too high of a level, they won’t succeed, and we will bear some of the responsibility. For each assignment or responsibility, do an analysis of where they fall within the levels, and then ask yourself, why not higher? What would need to happen in order to move them into higher levels?

To help with this analysis let’s consider four different factors that limit someone’s placement within the Levels of Delegation. For each factor, I’ll describe what it means and offer you some food for thought, so that you might think about the conditions that will allow them to advance up the scale.

Limiting Factor #1: Experience

Sometimes people are low in the levels of delegation simply because they lack experience or familiarity with the subject matter. How will they get good at presenting to executives if they’ve never presented to executives? How will they become comfortable responding to incidents if the tech lead is always jumping in with the solution?

Ask yourself: What kind of mentorship, educational resources, or opportunities do they need to help them gain familiarity and experience?

Limiting Factor #2: Complexity

Sometimes people already have familiarity with a responsibility, but only in simpler contexts. Ratcheting up the complexity of a task is a good way to stimulate growth – but it can also be a recipe for failure if, like so many things at work, we delve into them and discover they are even more complex than we initially thought. The trick is finding something with the right level of complexity.

Ask yourself: Is there a way to reduce, either marginally or temporarily, the complexity of the task? Can you reduce scope, offer additional resources, or have them further delegate in order to make this task more manageable? But also, can you just give them more time to figure it out, knowing that this will pay off in the future?

Limiting Factor #3: Trust

We might keep people in lower levels until they’ve proven their ability to own and deliver on something. It could be that they have not yet earned our trust, or that they’ve previously broken it (perhaps by failing to deliver in such a way that we are concerned about future delivery). It’s natural for us to feel cautious in these situations, but it’s also important that we grant trust to our team and allow people to recover from past mistakes.

Ask yourself: How will you give them the opportunity to earn (or regain) trust? How can you ensure that you’re fairly evaluating them and not succumbing to potential biases? What checkpoints could you put in place that will give both you and your direct reassurance that things are on the right track?

Limiting Factor #4: Control

One of the biggest traps we can fall into as managers is refusing to let go of control. Sometimes it’s valid – let’s say you’re delegating something to a team member that has C-suite visibility, and the CEO is notorious for holding grudges. You may want to maintain a level of involvement to ensure the success of the project and to provide air cover. However, often we keep people in the “I decide” or “We decide” categories for longer than necessary because of our own fears. We might be unwilling to let someone do things their way, or we might be concerned that letting go of control means that something takes longer than it would if we were to dictate the solution ourselves. However, this tendency is something that not only limits our team members’ growth, but our own growth as well. Like the tech lead who’s always jumping in to solve engineering incidents, your refusal to fully delegate responsibility means no one else learns how to take over, and you will always get stuck holding the baton.

Ask yourself: Why do you need control for this responsibility? How can you experiment with letting go of control, a little at a time? What will you need to see to fully relinquish control?

There are four steps to the worksheet:

Strengths/Gaps Analysis: Identify their biggest strengths (which can be leveraged for their growth), as well as their gaps (which might accelerate their growth once addressed). You might consider reviewing prior performance reviews, talking to their peers, and/or having them self assess in order to gain a comprehensive picture of their performance.

Expansion Opportunities: Identify opportunities that will help them expand in 2 or more of the expansion categories (skills, scope, complexity, business impact, and influence). This should help you identify at least one stretch assignment to delegate to them.

Delegation Level Analysis: Choose one of their existing responsibilities. What is the current level of delegation for this responsibility? Of the four limiting factors (experience, complexity, trust, and control), which factors are preventing them from moving higher in the levels? Do the same analysis for your stretch assignment. (Hint: the level of delegation for your stretch assignment should probably be in the 1-5 range if it’s truly a stretch.)

Increasing Delegation Levels: For both the existing responsibility and the stretch assignment, consider the limiting factors and ask yourself how you can gradually move them just one level higher.

Note: This content is available in both a talk format and as part of the Developing Your Team Members workshop. To inquire about speaking fees or workshops, please click the button below.